NELA ARIAS-MISSON

(1915-2015) was a Cuban-born painter whose work extended over fifty years and overlapped significantly with The New York School. She exhibited internationally and was friendly with many artists of the period, including Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Karel Appel, Walasse Ting, and Antoni Tapies. She studied with Hans Hofmann at his schools in New York City and Provincetown and forged a reciprocally kind attachment to him, thriving under his tutelage. She diligently followed Hoffman's instruction, as evidenced by her countless figure drawings of the 1940s and 50s and her adoption of abstraction as an "arena" for action. Arias-Misson was striving to put a form in space, using the rectangle as a virtual theater while working spontaneously. Hofmann encouraged a deep visual illusion grounded by the figure in space. Arias-Misson became entirely proficient in the language, and understandably her work in the 1940s and 50s followed a modernist orthodoxy. Arias-Misson painted like many of her peers with a flair for immediacy and rawness. However, her physical application of paint set her apart from most of them. In the longer run, and after she left NYC for Spain in 1961, Arias-Misson moved into unchartered waters and developed some most astonishing paintings in her later years. Her vision is so unique and startling that she upends art history as we know it. This exhibit is dedicated to making a case for Arias-Misson: how she evolved artistically and why she has been largely overlooked. As she once predicted: "When the time comes, something will happen." That time has arrived.

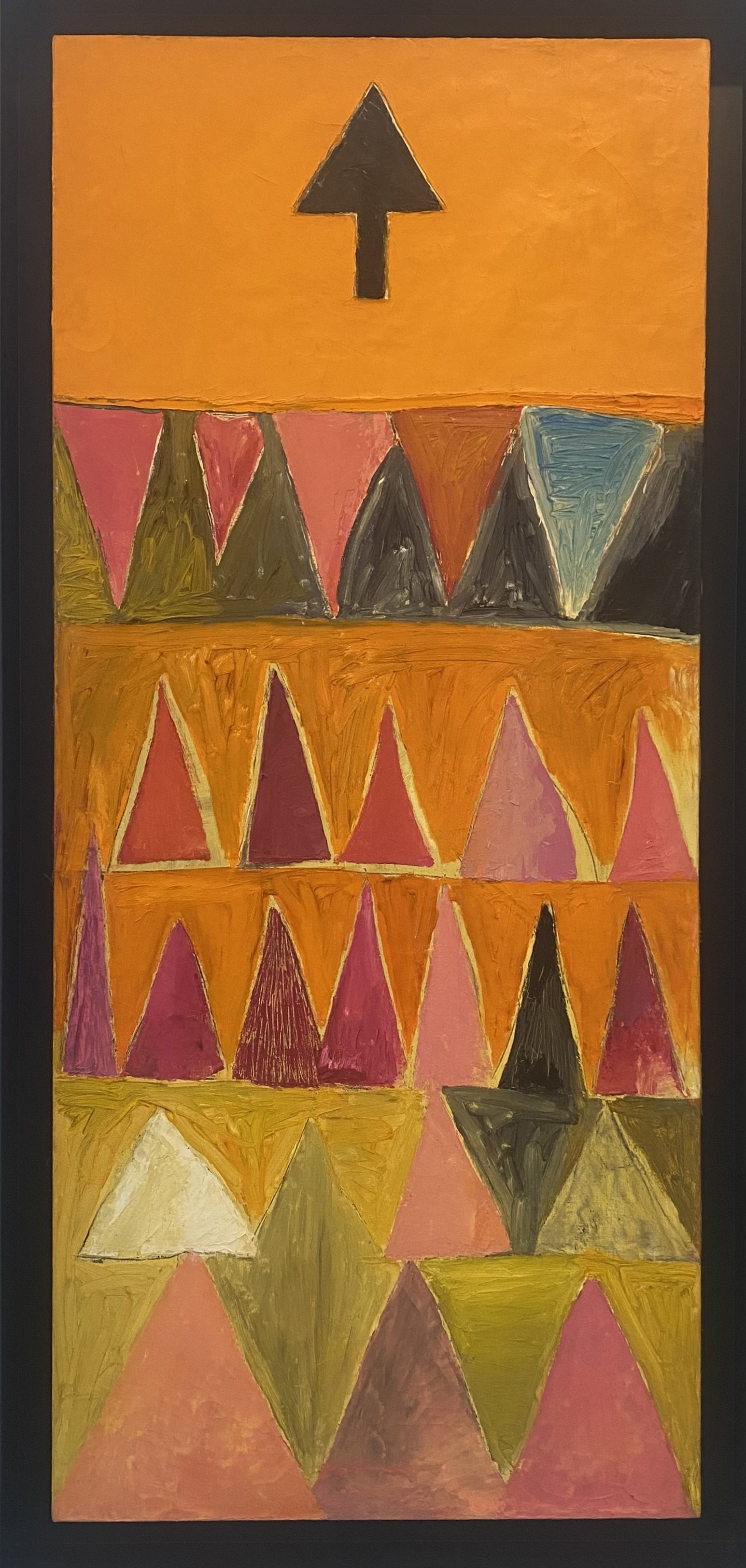

For Nela Arias-Misson, the precondition for painting was a theatrical force bearing the mark of Hofmann's belief in nature, physicality, and drawing. For the time being, she depended unequivocally on his assertion that abstraction was the ultimate vehicle for articulating meaning. In 1960, Nela Arias-Misson departed NYC for Ibiza, one of Spain's Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea and launched a new conversation about painting. In hindsight, she made a good decision to leave the NYC art world as the ensuing years resulted in ideological clashes that served no one. Abstract painting in Europe, specifically Spain, was gaining traction with less obvious outcomes and less notoriety, with the exception of the great master Joan Miro. The urgent posturing of NYC must have felt far away for Arias-Misson, and she established a very different tempo in her work. Her most essential inventions start now. The paintings she made generate a gravitational pull, and these mysterious objects demand closer inspection. Each painting is a story filled with quixotic associations. Arias-Misson employs a far more reductive attitude in these works and compresses the energy of her earlier work (she sublimates it) into magical constructs that appear playful, comic, and intimate. For instance, Untitled, 1961 is a smallish composition with an almost ultramarine blue ground and six brightly painted orbs on the surface; an ochre shape at the bottom of the painting suggests a sizable circular form penetrating from the bottom. Everything about this work is planetary, but an intimism throughout the painting holds off that early association. While her abstractness could be traced to Hofmann, something else happened: Arias-Misson shifts gears and applies paint with even greater physicality. She adopts an industrial strain like a house painter, a plasterer, a masonry trowel, and a bricoleur. Arias-Misson is overcome by thingness, finding brilliant forms that smile and sing. The paint handling is as tough-minded as Gaudi’s sculpturesque architecture. Defiantly, Arias-Misson challenges the conventions of her master Hans Hofmann, and her sense of adventure drives her to even greater extremes as she places her faith in authenticity and self- awareness.

If balanced against the NYC art in the early 1960s, Arias-Misson’s evolution or timeline conformed with Robert Ryman, a painter she did not know, and trails behind Agnes Martin by a few years. While some parallels could be drawn between these artists and Arias-Misson, her intentions were hardly about asceticism. Arias-Misson reveals a growing symbolic activity, conveying paradox and passion. The paintings read like allegories; each work becomes a character with theatrical aspirations. Figure Humaine from 1968 is gripping and reads like a cave painting of Teletubbies. But the tone is dead-serious and is coupled with the suspense of an awakening or divine intervention. If Arias-Misson was looking to do God’s work, her paintings come very close to just that.

In 1963, Nela had married Belgian poet-novelist-artist, Alain Misson: they both used the surname Arias-Misson. Alain Arias-Misson, a co-founder of the visual poetry movement, collaborated closely on projects and performances with many European artists. The Arias- Missons lived in Europe until 1976 when they returned to the United States and moved to a rural part of New Jersey. Nela Arias-Misson continued to paint but lived quietly and withdrew from the art world. She exhibited occasionally. In 1993 she was in an automobile accident that required major surgeries on her left arm, and she was no longer able to paint as before. In 1995 Nela moved to New York City where she lived until she made her final move in 2002 when she settled in Miami.

Arias-Misson lived daringly. Her creative metamorphosis speaks to her individuality and utmost respect for painting. She set a high bar. In the late 1960s, formal abstraction was taken down by Philip Guston's infamous exhibit at Marlborough Gallery in 1970. Younger artists bolted from their previous postures and religiously adopted this new narrative of painting. Guston was the progenitor of New Image Painting: Jennifer Bartlett, Jonathan Borrofsky, Susan Rothenberg, Louisa Chase, et al. But Arias-Misson was more likely the legitimate predecessor of these artists. Her challenge to Hoffman's conventions was Oedipal in scale; she internalized what she needed and discarded the rest. Her paintings are preconscious and fueled by fantasy, like living dreams. They are allusive and fictionalized, evoking an otherworldliness captured, set apart, and isolated. Arias-Misson took painting to a moral plane by exploring her world and then going beyond what we know. She employs a degree of absurdity as she navigates the here and now. She laughs in the face of fear and dread while conjuring images of extraordinary delight; her view remains saintly and playful. Arias-MIsson freed herself from any known rules regarding painting and entered a fantasy world without any skepticism or doubt. She found her images, all of them essential, and created her destiny.